2 books by Marouan, Maha

Race and Displacement

Nation, Migration, and Identity in the Twenty-First Century

Edited by Maha Marouan and Merinda Simmons

University of Alabama Press, 2013

Race and Displacement captures a timely set of discussions about the roles of race in displacement, forced migrations, nation and nationhood, and the way continuous movements of people challenge fixed racial definitions.

The multifaceted approach of the essays in Race and Displacement allows for nuanced discussions of race and displacement in expansive ways, exploring those issues in transnational and global terms. The contributors not only raise questions about race and displacement as signifying tropes and lived experiences; they also offer compelling approaches to conversations about race, displacement, and migration both inside and outside the academy. Taken together, these essays become a case study in dialogues across disciplines, providing insight from scholars in diaspora studies, postcolonial studies, literary theory, race theory, gender studies, and migration studies.

The contributors to this volume use a variety of analytical and disciplinary methodologies to track multiple articulations of how race is encountered and defined. The book is divided by editors Maha Marouan and Merinda Simmons into four sections: “Race and Nation” considers the relationships between race and corporality in transnational histories of migration using literary and oral narratives. Essays in “Race and Place” explore the ways spatial mobility in the twentieth century influences and transforms notions of racial and cultural identity. Essays in “Race and Nationality” address race and its configuration in national policy, such as racial labeling, federal regulations, and immigration law. In the last section, “Race and the Imagination” contributors explore the role imaginative projections play in shaping understandings of race.

Together, these essays tackle the question of how we might productively engage race and place in new sociopolitical contexts. Tracing the roles of "race" from the corporeal and material to the imaginative, the essays chart new ways that concepts of origin, region, migration, displacement, and diasporic memory create understandings of race in literature, social performance, and national policy.

Contributors: Regina N. Barnett, Walter Bosse, Ashon T. Crawley, Matthew Dischinger, Melanie Fritsh, Jonathan Glover, Delia Hagen, Deborah Katz, Kathrin Kottemann, Abigail G.H. Manzella, Yumi Pak, Cassander L. Smith, Lauren Vedal

[more]

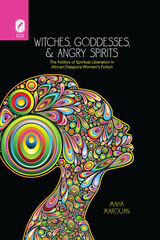

Witches, Goddesses, and Angry Spirits

The Politics of Spiritual Liberation in African Diaspora Women's Fiction

Maha Marouan

The Ohio State University Press, 2013

Witches, Goddesses and Angry Spirits: The Politics of Spiritual Liberation in African Diaspora Women’s Fiction explores African diaspora religious practices as vehicles for Africana women’s spiritual transformation, using representative fictions by three contemporary writers of the African Americas who compose fresh models of female spirituality: Breath, Eyes, Memory (1994) by Haitian American novelist Edwidge Danticat; Paradise (1998) by African American Nobel laureate Toni Morrison; and I, Tituba, Black Witch of Salem (1992) by Guadeloupean author Maryse Condé.

Author Maha Marouan argues that while these authors’ works burst with powerful female figures—witches, goddesses, healers, priestesses, angry spirits—they also remain honest in reminding readers of the silences surrounding African diaspora women’s realities and experiences of violence, often as a result of gendered religious discourses. To make sense of Africana women’s experiences of the diaspora, this book operates from a transnational perspective that moves across national and linguistic boundaries as it connects the Anglophone, the Francophone, and the Creole worlds of the African Americas. In doing so, Marouan identifies crucial shared thematic concerns regarding the authors’ engagement with religious frameworks—some Judeo-Christian, some not—heretofore unexamined in such a careful, comparative fashion.

[more]

READERS

Browse our collection.

PUBLISHERS

See BiblioVault's publisher services.

STUDENT SERVICES

Files for college accessibility offices.

UChicago Accessibility Resources

home | accessibility | search | about | contact us

BiblioVault ® 2001 - 2024

The University of Chicago Press